As time has passed since lockdown we have had more and more reports of an increase in challenging behaviour from students on social media channels such as Twitter and in our conversations with fellow front line teachers.

That experience was certainly the case for our founder, Neil Moggan when some of the young people he was working with were struggling with intergenerational trauma, trauma from covid and also trauma caused by wider instability in the school to create significant behavioural challenges in the summer term of 2022.

In this week's blog we are exploring how relationships with our most challenging young people can be transformed through our body language and the way we manage conflict.

It resulted in Neil reducing the number of students sent out from his classes in one term by 95% and led to transformed relationships, greater student/staff wellbeing and children thriving in their academic progress. Neil takes up the story here:

Trauma taking its toll

As we returned to education in a post covid world, like many schools across the country, the pandemic had taken a significant toll on staff, the children we serve, our local community, and there was considerable instability and disruption.

For the first time in my teaching career I was struggling to build the quality of the relationships I wanted with my young people, particularly with my most challenging children. I was using a ‘Choices and consequences’ policy employed by the whole school and it wasn’t working for me as it had done pre-pandemic.

I would get short term results by following the process and eventually removing the child from the class but by this time everyone in the class had been impacted in a negative way affecting their learning, and theirs and my wellbeing.

Despite restorative conversations taking place, in some of the lessons that followed the same child often reoffended as we didn’t quite trust each other and the cycle continued and deepened. I was dealing with the surface problem rather than showing empathy and looking deeper.

The sanctions that followed, such as isolation rooms, were potentially retraumatising these young people, and the whole process was disengaging them from their learning and leading to them resenting their teachers and school.

I was pulling my hair out with frustration at the situation, I had never been so committed to improving my children’s mental wellbeing but all I was doing was making the situation worse!

Finding a solution in psychological safety

I had to find a solution as my current strategies just weren’t working in my setting anymore, I had to find a way of getting my most challenging children on side by rebuilding our relationship, developing trust, getting them to feel psychologically safe and enjoying school, and engaging them in their learning.

I enrolled onto the Diploma in Trauma and Mental Health-Informed Schools through Trauma Informed Schools UK and started experimenting with a range of strategies aiming to achieve the above.

Firstly, I started by helping my young people feel psychologically safe through an ultra positive meet and greet and by using my body language to increase safety cues. Our face, voice and body are crucial to this. When it is successfully actioned we trigger their social engagement system rather than their social defence system.

Culling unnecessary rules

I reviewed the department rules and got rid of any unnecessary ones to reduce the chances of conflict. We had a rule that children had to take their school shoes off to keep the dance floor clean. This meant my meet and greet would involve looking at children’s feet and challenging those who refused to take their shoes off.

It was an unnecessary rule that triggered their social defence system. I was getting fed up and annoyed with the constant whinging about why they had to take their shoes off and it was getting the lessons off to a bad start on a regular basis.

Are there any unnecessary rules you could remove?

The 3 model sequence

The second step was to apply 3 models in sequence to de-escalate situations and deal with them effectively without lowering standards.

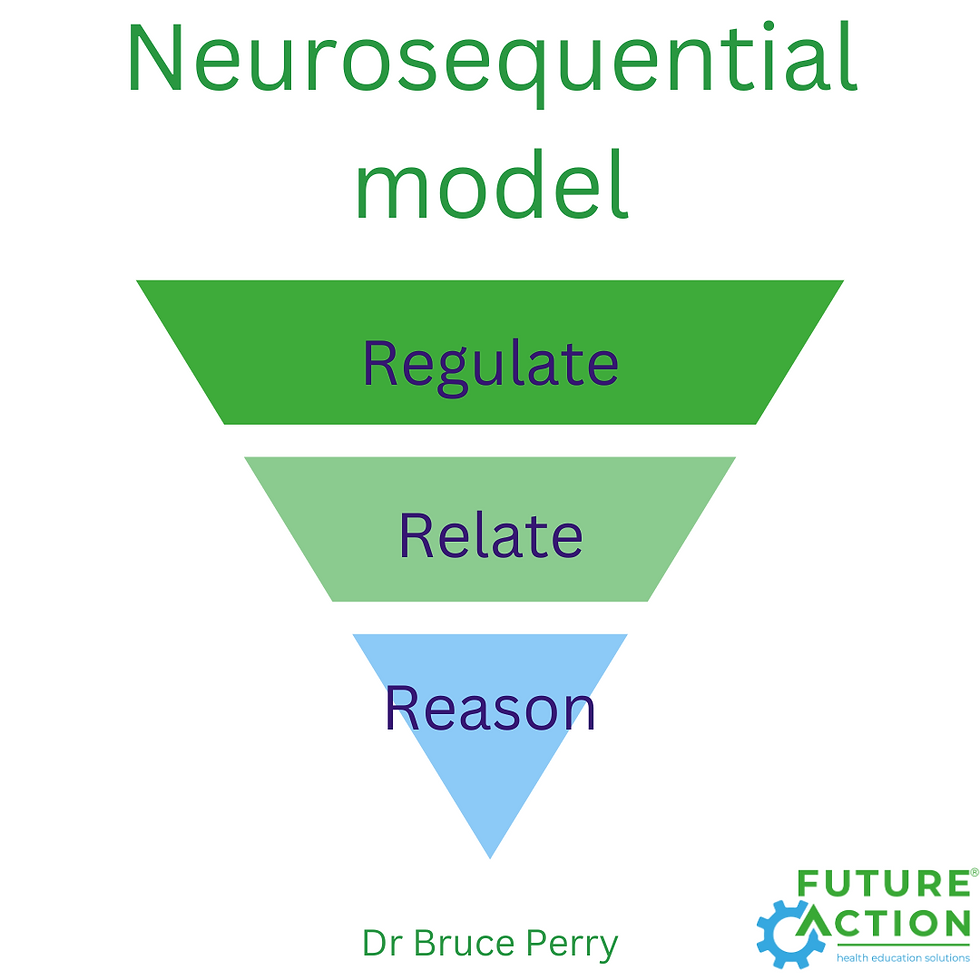

The Neurosequential model

The first model I applied was the Neurosequential model created by Doctor Bruce Perry. This helped me understand how a child’s brain works, and helped stop me getting frustrated when a child didn’t respond as I wanted because their body wasn’t in a position to access the parts of their brain required to respond in the way I requested.

By understanding how the child’s brain works it gave me greater patience and I understood the steps that were required to get the outcomes we wanted.

Firstly, I had to help the child to ‘regulate’ to calm their fight/flight/freeze response. I then needed to ‘relate’ and connect with the child through an attuned and sensitive relationship.

Thirdly, I needed to ‘reason’ with the child to support them to reflect, learn, remember, articulate and help them become more self-assured.

Previously, I was heading straight to the ‘reasoning’ part of their brain focusing on my expectations of learning and this was not working for children who were dysregulated and feeling disconnected from others. The result was inevitably failure for both myself and the child.

Pace model

I then used Doctor Dan Hughes' PACE model as the next stage. PACE is a way of thinking, feeling, communicating and behaving that aims to make the child feel safe by activating their social engagement system. PACE stands for Play, Acceptance, Curiosity and Empathy.

Playfulness

Sometimes, playfulness was useful for diffusing situations by de-escalating them rather than ramping them up. It is not banter but it lightens the mood and triggers the child's social engagement system so that they can access the part of their brain to make better decisions. It is not always appropriate to use but it can be great for the right situation.

I was on-call one day when a group of girls were truanting and refusing to follow a colleague's instructions, one girl in particular was freaking out about her eye lashes. I made a light hearted quip about my eye lash treatment regime, it made her smile and my colleague and I managed to diffuse the situation and get the girls feeling psychologically safe and back on track with their learning.

It was a critical intervention, the young lady had been suffering massively from grief following the bereavement of a close family member and it opened the door to the start of a closer relationship rooted in acceptance and empathy that made her feel psychologically safer in school.

In the days and weeks that followed I would regularly check in with her to check she was ok. Sometimes, that would be verbally, other times a simple thumbs up from across the room. I was trying to offer those safety cues to reassure her and help keep her on track.

Acceptance

Accepting was critical for me as the poor behaviour and my lack of control over it in the summer term was having a real impact on my own wellbeing. I accepted the children’s behaviour for what it was and being curious why, rather than taking it as a personal slight. It took away my need to win the behaviour battle and reduced my personal frustration significantly.

It enabled me to have greater empathy and look deeper at the causes rather than wondering why they were trashing my lesson and triggering my own social defence system. It was a gamechanger and improved my wellbeing straight away.

Curiosity & empathy

Being curious helped me look deeper and walk a mile in my young people’s shoes rather than purely from my perspective of what outcomes I wanted for my department and school. I looked deeper at the issues they faced, what they had been through and what was triggering this challenging behaviour.

It resulted in greater patience from me, improved body language and a calmer tone which got better results. I invested in our relationships and the things that mattered to them, I was emotionally available to them and this reduced the frequency and severity of the behaviour incidents that followed in the coming weeks and months.

I developed greater empathy for my most challenging young people. I stopped trying to fix everyone’s problems and just listened. As teachers we love to fix people’s problems but sometimes problems are so big that we can’t fix them and that is ok. I couldn’t fix the girl’s grief who lost her loved one but I could let her know that I was here for her anytime she wanted to talk, I was thinking about her and I cared about her. She later told our school counsellor how much that meant to her to know a teacher cared.

Aren’t trauma informed behaviour policies to wishy washy?

Some critics argue that trauma informed behaviour management strategies encourage lower standards and are hard to implement with large numbers of children, for example in secondary school settings where you could have schools with well over 1000 young people.

The solution for me was using the Nurture-structure highway as a way of getting the right balance. The Nurture-Structure highway was created by Jean Illsley Clarke.

Think of a motorway with 3 lanes. On the inside lane we have nurture and on the outside lane we have structure. We want to stay in the middle lane, we definitely do not want to be in the field either side of the motorway.

Structure is important because when we structure routines, systems and teaching strategies to create the right conditions it enables students to be successful.

For example, calm and orderly routines around changing, consistent, predictable structures to lesson content all build trust and reduce the potential for dysregulation. This maximises opportunities to build relationships so that young people can thrive.

However, we don’t want to veer so far over to structure that routines are so heavily fixed that there is no leeway for individual situations leading to the young person feeling psychologically unsafe, restricted and alone.

On the other hand, we don’t want to veer so far over to the other side of nurture that there is no level of challenge to misbehaviour and the young person thinks they can do whatever they want without consequence, as that is not going to do them any favours, especially when they go into wider society.

By using my understanding of the Neurosequential model I would have conversations with a young person when they were in the right head space to have the greatest impact moving forward without retraumatising them to make sure I got the balance right.

As we experimented, we found that the highway balance depended on the class, the individuals and their experiences of trauma. Some groups needed more structure, some needed more nurture to get the balance right. No one knows your young people better than you so the challenge for you is to find that right level for your individual classes and school.

Outcome on individual students and class as a whole

By placing relationships first, and connecting before correcting, my relationships with all children I teach have been transformed. In particular my most challenging young people feel psychologically safer so they are calmer. This creates an enhanced environment for all young people to learn and thrive in.

My most challenging young people are happier & healthier, and their behaviour has improved significantly over a period of time. There are still behavioural issues now and again.

Working with children who have suffered from trauma is never straight forward but our children are more engaged in their learning leading to an increase in progress, and my own wellbeing has improved considerably.

Success for John

I was really proud of one of my students in Year 9, called John, who struggles massively with shame, dissociation and rage. He was frequently being removed from lessons for his behaviour in the wider school. John would often arrive in my class in a very wobbly way intent on getting sent out of the lesson.

By utilising these combined strategies, John has made huge strides, he is engaged in his learning, we work out together in the fitness suite to push away his stress and anger and he is in a much better place. When John said ‘I have used muscles I never knew I had sir and I feel so much calmer’ it gave me that special buzz that lets you know you are in the right place.

Saving time

As teachers, we are in constant battle around the effective use of time. I hated having restorative conversations with children and parents, it was the last thing I wanted to do at the end of the day, I’d much rather be running clubs and fixtures, and thinking about how I could improve the department.

Previously, it felt like I’d be punished three times when dealing with misbehaviour. Once, when the child wrecked my lesson, secondly, having to take time from my day to have the restorative conversation with the child and thirdly, when I had to call the parent to give them the bad news.

Instead I choose to invest my time up front in being emotionally available and investing in relationships with my most challenging children. Rapidly, it saved me time, particularly within a lesson and at the back end of the day. My vocation became a lot more enjoyable in the process.

Trauma informed blogs

If you would like to catch up on our previous blogs on implementing trauma informed practice in Physical Education, they are here for you:

Over the coming months we will continue to develop trauma informed insights such as:

How we can widen a young person’s window of tolerance in Physical Education

How play can be a vital tool in improving mental wellbeing in Physical Education

How you can take trauma informed practice from your classroom to your wider school to have greater impact

We hope you found this week's blog insightful, we would love you to join our community of teachers committed to transforming the life chances of their children. Please make sure you subscribe to our newsletter to join us so you don’t miss the next edition.

Join us at the Youth Sports Trust Conference

Neil will be presenting at the Youth Sports Trust conference to share how we can use a trauma informed approach in PE to prevent and improve mental health issues for young people.

We would love for you to join us on March 2nd in Telford. Click here to find out more about the conference.

Comments